|

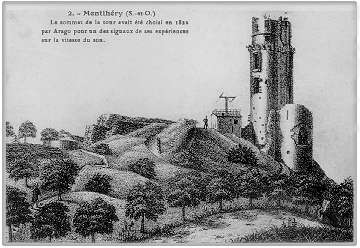

Montlhéry, cité millénaire.

Aujourd'hui :

|

|

The Montlhery castle by J. -C. Guillon

© J.-C. Guillon, RAG n°2,

APEA,

1996.

(Translation work carried out by Christine Kaminski in 1999)

- French text

INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION

This article is the summary of a master work carried

out in 1995 and from a postgraduate work carried out in 1996 on

the Montlhéry castle.

It was necessary to begin by tracing the chronology

of the area. By doing this, we were able to restore the different

phases of construction of the fortress, all in keeping it within

the study of the regional fortification. The objectives of this

work are to analyze some of the architectural elements and the reconstruction

of the castle in three dimensions, linking it to the different key

periods of its existence.

2. THE MONTLHERY CASTLE - HISTORY

2. 1 From the Neolithic age to the end of

the Early Middle Ages :

There is proof that the area was indeed inhabited

in the Neolithic age. Cut and polished stones have been found, as

well as numerous potteries, throughout the region, which testify

that the first men who stayed there actually stayed in the Neolithic

courtyard. On the other hand, no element has been discovered at

the actual site of the castle.

At the Gallo-Roman period, the region of Montlhéry,

was part of the Aequaline forest, which contained in its center

the vague boundaries between Parisii, Sénons, and Carnutes. It also

had the Roman road from Paris to Orleans passing through it, which

crossed at the foot of Montlhéry, in the actual commune of Linas.

The existence of a vicus road linked at the crossing

of water, which is situated at the foot of the steep mound of Montlhéry

is proven by the discovery of a Gallo-Roman and Merovingian cemetery

in 1890 and in 1981 in Linas.

The funeral furniture contained in the approximately

ten tombs that have been found to this day date to the second and

fifth centuries. The examination of the first tombs gives us an

almost certain proximity of the housing, from the findings of pieces

of broken domestic ceramic and tiles in the clearings. The housing

became stretched out towards the west and the south along the Roman

road. This main road of communication passed in front of the Saint-Merry

church and crossed the Sallemouille stream, at the foot of the mound.

Since then, this very marshy place has been cleaned up.

There is proof at the site of the Saint-Merry church,

which was built on the Gallo-Roman and Merovingian cemeteries, of

a permanent habitation in this area during the Merovingian and Carolingian

periods. Also, the Saint-Merry church, known by the records of the

Carolingian period, could have a Merovingian origin, since the term

Saint-Etienne suggests a date of higher foundation.

This concentration of habitat in the valley bottom

reflects the reality of the populating of Essonne at the Low-Empire

and at the Early Middle Ages. The large communication roads that

pass through this sector have constituted one of the elements of

settling some of the population.

This veritably known history of Montlhéry, begins

in 768 AD, a period in which the Abbey of Saint-Denis received from

Pépin the Short "Aetrico monte cum integritate". The donation

of the Montlhéry mound is confirmed by an act of Charlemagne in

774.

Later, according to oral traditions, Montlhéry

had been exchanged for some other ground belonging to the bishops

of Paris, and then it became one of their fiefdoms. One of them

gave themselves up to the knights, which later became his vassals.

2.2. THE COUNTS OF MONTLHÉRY(991-1118AD)

2.2.1 Thibaud Tow-Head (File-Étoupe) and his

close descendants (991 - 1105 AD)

The first lord of Montlhéry was Thibaud, whose

pale blond hair gave him the nickname Tow-Head. He was one of the

principle barons of Hughes Capet, and of King Robert, who followed

after Capet. He was responsible for taking care of the forest, which

was an important function, and which also included being Master

of the Royal Hunt, supervising the waters, forests, wolves, and

falcons.

A continuing text called "l'Historia Francorum

" from Aimion de Fleury says:

"Temporis Roberti regis, Theobladus cognomine

Filans Stupas, forestarius ejus, firmavit Montemlethericum".

So Thibaud fortified the mount around 991 AD, undoubtedly

for political reasons. In effect, the royal domain of Robert the

Stakes (Le Pieux), which included Montlhéry, was not a united region.

In the west and south zones of his domain, the king had to deal

with the scheming from the counts of Blois. The Capetian had to

dispose the strong points in order to block the maneuvers of the

Blois house. Montlhéry was, without doubt, one of these bases.

The

castle only consisted of a tower of isolated wood, protected by

an enclosure; and though it once soared into the sky from this mound,

today much of it is left in ruins. Thus we call it the Montlhéry

lump. The

castle only consisted of a tower of isolated wood, protected by

an enclosure; and though it once soared into the sky from this mound,

today much of it is left in ruins. Thus we call it the Montlhéry

lump.

Always, according to the account of Aimoin de Fleury:

"Ipse (Theobaldus Filans Stupas) habuit unumfilium

nominatum Guidonum, qui accepit in uxore dominam de Feritate et

de Gommet. Idem Guido genuit ex ea Milonem de Brayo et Geidonem

Rubeum".

From this text we learn that, at the time of King

Robert (996 - 1031 AD), Guy, son of Thibaud Tow-Head, married the

lady of Ferté and Gometz. From this union, Milon of Bray and Guy

the Red were born.

It seems certain that Guy was brought up at Saint-Pierre

priory, close to the castle as well as the Notre-Dame church, which

first served the parish occupants of the town. His wife Hodierne

established a monastery at Longpont in order to serve the domestic

necropolis. However, Guy the First of Montlhéry gave his children

in marriage to the most noble families of France: Milon, his oldest,

married Lithieuse, viscountess of Troyes; Guy the Red, his second

son, was count of Rochefort; Guillaume, the youngest, was lord of

Gometz; his first daughter MéIisende, married the count of Rhéteil;

MéIisende the young, the lord of Pont-sur-Seine; Elisabeth was the

wife of Josselin of Courtenay; Alix married Hughes, sire of the

Puiset; and his youngest daughter was to be married to Gauthier,

count of Saint-Valery.

Guy the First did not obtain lordship until after

his death because, wanting to die a Christian, he left it to his

son Milon and retired as a simple monk in the priory of Notre-Dame

of Longpont.

It seems as though Milon the Big did not show himself

devoted enough to his father, Philippe the First; in effect, several

times he formed a league with the prince's enemies. Thus Philippe

the First comprised an important strategy from the castle which

controlled all the communication between the two Capetians towns,

Paris and Orléans. He tried to obtain the fortress by exchange or

purchase, but without success. Fortunately, the crusades came to

his aid.

Milon the Big left during the first crusade (1096

- 1104) with his oldest son, Guy Troussel; his brother guy the Red,

count of Rochefort; and his nephew Hughes, sire of Crécy, who was

the son of Guy the Red. It is possible to date their departure to

1096 since Guy the Red, also the seneschal, disappeared from these

events around 1095, and did not reappear until 1104.

We know the results of the voyage from the accounts

of the Abbey Suger. Guy Troussel abandoned the holy business and,

unbeknownst to his father, he escaped from Antioch, which was besieged

by the Corboran army. He then returned to France.

With the crusade now finished Milon the Big was

reunited with his dishonored son. He then set off once more for

holy ground where he was killed at the battle of Ramlah in 1103.

Guy Troussel then became lord of Montlhéry. However,

being removed from everything, he lived in constraint, no reaching

the recommendations of Philippe the First. He agreed to leave the

castle on the condition that the king of France marry his natural

son, Philippe of Melun, to Elisabeth, his only heiress. The marriage

was celebrated in 1104.

According to Suger, King Philippe the First said

to his son Louis, "Go, Louis, my child; be well-attentive to

conserve this tower. The humiliation nearly killed me, as well as

the trickery and criminal fraud which never let me have peace or

an assured repose."

So, in 1104, the castle of Montlhéry was once again

crowned with a lord.

2.2.2 LOUIS VII AND MILON (1105-1118AD)

During this time period, the Montlhéry castle was

a theatre of grand events which had a contemporary historian: Suger,

who was the Abbey of Saint-Denis and a friend of Louis VII, and

who wanted to write about its life.

Here is what is said about Montlhéry and its lords:

Milon, viscount of Troyes and baby brother of Guy

Troussel, along with the Garlande brothers and other barons, introduced

himself and his soldiers to Montlhéry. Welcomed into the castle

with the understanding that he would stay there, he raised up a

garrison, saying, "These armed traitors rush towards the tower,

attacking those who defend it, and fight so sharply with fire, bows,

spears, lances, and stones, that in several places they breach the

outer ramparts of the tower and mortally wound many of its defenders".

In this tower were the refugees Alix of Rochefort, the wife of Guy

the Red, who was the seneschal of France, and her daughter Lucienne,

fiancée of the king's son. Guy the Red prepared a troop in order

to deliver his own people. Those who attacked the tower were unable

to seize it and ran off at the sight of the ost(army) of Guy the

Red. The seneschal skillfully knew to detach the Garlande brothers

from the league of lords, and Milon of Troyes, his nephew, was abandoned

by all and went to hide his shame and anger in his domain.

Louis VI, upon returning to Montlhéry, confirmed

the peace agreement signed between Guy the Red and the barons, but

prudently he destroyed all the fortifications with the exception

of the tower.

One of the first acts of Louis VI, who became king

in 1108 at the death of this father, was to remove the dignity of

stewardship from Hughes of Crécy, son of Guy the Red, in order to

give it to Anselme of Garlande, whose brother Etienne received the

order of chancellor. He presented the ground and the castle of Montlhéry

to his natural brother, Philippe of Melun. But Philippe gave the

castle back to Hughes of Crécy, to surround the king of enemies.

Hughes hurried towards his new lordship once the king threw himself

into his pursuit. During these days the two adversaries were in

opposition; one to have his lordship and the other to stop him.

Milon II of Bray, who was the cousin of Hughes, demanded the lordship

by right of heredity. So the king offered Milon II the lordship

of the townspeople, who then fought against Hughes in expelling

him from the castle, threatening to kill him. Hughes was thus forced

to run away.

To continue here, it is necessary to recover the

"Chronicle of Morigny", where it is written that:

Hughes was furious from being forced to leave the

Montlhéry castle by his cousin Milon who got it back by right. This

is why he ravaged the surroundings. A little later, he successfully

seized the castle thanks to treason. He then imprisoned Milon II

in his Châteaufort tower. One night, "taken by folly",

according to the chronicle, Hughes strangled his cousin with his

own hands, then threw him out of the window, perhaps to make it

look like an accident. The royal reprise did not wait: the king

rushed to the Gometz castle and rapidly overtook it. Hughes, taken

in fear and panic, was summoned to appear in the court of his lord.

This passage is interesting because we learn that

his lord is in fact Amaury IV of Montfort, gruyer(royal officer

for forest and water) of the Yvelines forest. No matter what he

was, Hughes of Crécy was brought in front of Amaury IV. Tearful,

he bowed down at the feet of his lord, gave him back the grounds

and assumed the monastic habit. All of this happened before the

death of Anseau of Garlande in 1118.

It was as if the Montlhéry castle came back under

the royal yoke after successively having had the lords: Thibaud

File-Étoupe, Guy the First, Milon the Big, Guy II of Troussel, Milon

II of Braye, and Hughes of Crécy.

2.3 THE PROVOSTS (1118- 1529)

2.3. 1. The organization of the provosty

The town of Montlhéry was considerably expanded,

extending beyond the ancient fortifications, which first surrounded

it, which were built by the lords. This town had two gates dating

from the time of Milon the Big; the one was called the Paris gate

and the other was called the Baudry gate. This agglomeration placed

much importance on the market, which was held on Monday of each

week. The Jews, having bought the authorization to set up there,

had an entire quarter to themselves; the Rue Des Juifs and rue du

Soulier Judas (Judas Shoe). This increase of the Montlhéry market

made the room to establish the provosts and guards of the castle.

Master of the Montlhéry castle, Louis VI, entrusted

the guard to a provost (proepositus regis), who, under the title

of chatelain, and later captain, came together with some of the

knights who came under the seigniory to look after the castle in

his absence. According to the texts, these men were entitled as

guards, provosts, or captains of the chastel, chastellenie and counts

of Montlhéry and they took an oath in the count's chambers, whenever

they were required to, upon the king's return.

At the time of the administrative reorganization

of the kingdom by Philippe-Auguste, Montlhéry became the seat of

one of the 78 royal provosts.

The Montlhéry provosty spread from the north to

the south: from Mons and Athis to Lardy and the Ferte-Alais; and

from the east to the west: from Vert-le-Grand to Angervilliers and

to Val-Saint-Germain. It also included the actual districts of Longjumeau,

Arpajon, and parts of Limours and Dourdan. The jurisdiction of the

provosty was exercised on more than 100 parishes, and on 133 fiefdoms.

Most of these fiefdoms belonged to the knights appointed under the

name of "Milites of Fisco montis Letherici". They had

to be guards of the castle for two months every year. Documents

have kept the trace of Guy of Valgrineuse, Beaudoin of Corbeil,

Payen of Saint-Yon....

2.3.2. The Royal Sojourns (1160 - 1 356)

Louis VII stayed at Montlhéry several times with

Suger, his minister, who recorded several charters, notably the

one in 1144, for the Abbey of Saint-Denis.

On the inside of the castle, there were, at this

time, two churches: one was the collegiate of Saint-Pierre, which

was cleared away by the secular canons; and the other was the parish

church Notre-Dame. These two churches were reunited in 1154 at the

Longpont priory, and the abbeys of Longpont appointed the parish

until Saint-Pierre was erected at the priory, specifically towards

the year 1420. They were united with the neighboring chapel of Saint-Laurent

and, from this time on, were no more than a single building.

After his return from the second crusade around

1160, Louis VII founded the leprosy hospital of Saint-Pierre in

the marketplace, to take care of the poor who were ill. Today it

is the general hospital. On the side of this establishment the Notre-Dame

Chapel of Mt. Carmel was constructed, which later grew to become

the parish church, under the term of the Trinity.

Phillippe-Auguste often lived at the Montlhéry

castle. At the request of Guillaume, who was the bishop of Paris,

he signed the trade letters by which he admitted to his debt over

the years to the diocese of Paris, which was the sum of 45 sous

for the fiefdom candles of Corbeil and Montlhéry, which were confiscated

and returned to the king. In 1184, he again signed a charter by

which he left one 10th of the bread and wine, which he consumed

while staying at Montlhéry to the abbey of Bois-des-Dames.

Before his reign (1223-1229), Saint-Louis stayed

several times with the queen Blanche de Castille in Montlhéry. In

1227, at the time of the conspiracy of the lords against the regent,

the king and his mother were sent back to Vendome to rejoin their

congregation; we know that the rebels advanced the troops towards

Etampes and Corbeil in order to raise up the young king. Louis IX

was already at Châtres (Arpajon) when Thibaud urged him, the count

of Champagne, to withdraw himself to the castle. Traditionally it

is said that the young king was hid in an underground passage, which

we can see today; the entrance is only a few steps from the tower.

The Parisians say that the sire of Joinville rushed

through a crowd to rescue the young king and his mother and take

them back to Paris. We attribute to Saint-Louis the construction

of one of the buildings of the castle's enclosure. In effect, at

his return from the crusade around 1256, he was raised up at the

left the esplanade entrance, at the chapel, which carries his name.

Jean the Good stayed at Montlhéry, during the first

years of his reign. He came in order to hunt. Philippe of Saint-Yon

was then captain and count of Montlhéry. The dauphin Charles, Charles

V, resided at the castle during the captivity of his father, notably

after having dissolved the assembly of the State Generals convened

by the ordinance on Dec. 28, 1355. He even dated an ordinance from

Montlhéry, on Dec. 5, 1356, relating to the immunities of the town

of Tournay.

2.3.3. THE 100 YEAR WAR (1360-1450)

The history of the Montlhéry, castle during the

hostility between the British, French, and Armagnacs against the

Bourgignons is heavily detailed in an account given by Victor-Adolphe

Malte-Brun, an account which is kept in the preserved archives.

In 1358, under the provosty of Jacques of Hangest,

the British besieged the castle without being able to seize it.

In 1360, the troops of Edouard III succeeded in occupying it, but

only for a short time because Charles VI named a new provost in

1365. In 1382, Olivier of Clisson received the guard and the master's

office of the Montlhéry castle.

He left the castle a catastrophe for Brittany after

Charles, who had a fit of dementia, wanted to have his constable

arrested. In 1409, the Armagnacs seized Montlhéry, but evacuated

it a year later, only to return and occupy it again the following

year.

In 1413, the Duke of Bourgogne chased them out

and reestablished the king's people. On Oct. 8, 1417, the Duke of

Bourgogne, Jean without Fear (sans Peur), withdrew towards Montlhéry.

Tannegui Duchtatel, the provost of Paris, became irritated by the

extorsions of the Montlhéry garrison on the region of Paris and

besieged the castle, overtaking it in 1418. After being taken, Montlhéry

always held the Dauphin party. With the departure of the Parisians,

the Montlhéry, garrison resumed looting. A 2nd siege of the Parisians

failed.

It wasn't until 1423 that Montlhéry, surrendered

to the regent, the Duke of Bedford. The fortress stayed in the hands

of the British until 1436. A captain of the bourgeois militia named

Gauvin Leroy gave the castlefort to Charles VII. Charles awarded

him; he named him provost.

The town continued to stretch out, mostly over

the marketplace and towards the route to Paris. The Notre-Dame chapel

of Mt. Carmel, which belonged to the general hospital, was enlarged

in 1400 and erected by the parish under the protection of the Saint

Trinity.

2.3.4. THE BATTLE OF MONTLHERY (1465)

It was in the plain which spread out between Montlhéry

and Longpont that the armies of Charles, who became count of Charolais,

after Charles the Rash (le Téméraire), and the king of France met

at the time of the war and formed the League of the good Public.

Philippe of Commines who assisted in this battle on the Charolais'

side, left a detailed account. It was a foreign combat: the army

of the king of France, strong with 30,000 well-armed home soldiers,

went back towards Paris under the commanding of the king himself.

When Louis XI learned that his adversary Charles the Rash, accompanied

by the count of Saint-Pol who directed the vanguard, descended in

haste to his meeting after having gone around Paris, he became hostile

towards his enterprise, in the hope of making his junction with

the forces of the Duke of Brittany, Francois II. Louis of Luxembourg,

who was the count of Saint-Pol, established himself in the castle

fort of Montlhéry, which barred the old route from Languedoc, the

route of Saint-Jacques of Compostelle. The vanguards of the king

of France traversed the Torfou forest in the north of Etampes, where

they found the king. The inevitable combat happened on July 16,

1465 in the morning in the plain of Longpont. The first skirmish

took place at the extremity of the Montlhéry village. The Bourguignons

set fire to one or two houses and forced the French vanguards to

move back. During this time, Louis XI amassed his troops behind

the castle. Charles the Rash then believed that he had won the party.

He moved forward with his archers. That is when the king's people

suddenly stood and riddled the approaching cavalry with arrows.

Charles only had one resource, and that was to take off passing

by the body of archers who dispersed themselves in the forest. Charles

continued on, persuaded that he had cut in pieces the king's army.

When he learned that, in reality, the combat pursued in Montlhéry,

he turned back with his escort and again found the bulk of the troops

that Saint-Pol regrouped. The contact was exhausted. Louis XI reassembled

the royal army, in good order. Guns were fired from each part without

large results. Louis XI and his troops were guided towards Corbeil

where the king spent the night. The Rash camped on the battlefield,

persuaded that the fight would resume the next day. In the morning,

he noticed that he no longer had an adversary in front of him. He

uttered aloud that he was the winner and took back the Etampes road.

Louis XI announced, from his side, that he was victorious. In fact,

the issue of the combat stayed doubtful. But the Bourguignonne army

considered this loss to Louis XI as one of the more superior losses.

The greatest assets of the king of France were superior to those

of his adversary.

2.4 THE ENGAGIST LORDS

2.4. 1. The System of Engagism

On April 6, 1529, king Francois I gave the ground

and the lord's estate of Montlhéry to Francois of Escars, lord of

Vauguyon and seneschal of the Bourbon, but with the option of buying

it back.

From this period, the châtellenie and county of

Montlhéry, ceased from directly belonging to the crown. At its head

were the administration and the revenues of the estate, which succeeded

one another from the engagist lords, who were obtained through the

king for a determined sum. But the king always stayed master of

these rights to buy back in order to dispose of the new according

to his good pleasure.

As long as the king had not exercised this right

of buying back, the engagist lord "was pleased at what was

to come by him, his advancements and having cause, of the ground

and estate of Montlhéry, his memberships and buildings, houses,

manors, census, and incomes. Justice: high, middle, and bottom;

the fiefdoms and, aumosnes and other accustomed charges."

He administered the provosty and châtellenie through

diverse officers. The most important was the provost, or sous-bailiff.

This position fulfilled the charges of the ordinary judge, or the

assessor of the civil and criminal lieutenant, of the investigator

and examiner, and of seer for the king. After him came: the public

prosecutor of the king, the assistant to the investigator; the substitute

of the king's public prosecutor, two guarantors of the auction;

the chancellor : the -steward to the real seizures; the receiver

of spices and consignments; the court clerk of the writing box;

the court clerk of the ordinary justice; the 22 prosecutors, which

were later reduced to 12; the four notaries, which, later in 1621,

were created in each one of the principle parishes which came under

the châtellenie; the seven bailiffs, which were later reduced to

three; the twelve royal sergeants, the complete sergeant and the

sergeants of the woods, the huntings, the waters, and the forests;

a wine steward for the king. A wine broker, a sworn surveyor, the

captain of the castle, a lieutenant of the Master's office, a captain

of the. buntings and finally a chaplain of the Saint-Louis chapel.

Montlhéry was the seat of one of the ancient bailiwicks

of the royalty composing the viscount of Paris. The provost of Paris

do not had any right of justice, but as bailiff of Montlhéry and

the other bailiwicks of the viscount of Paris.

From an ecclesiastical point of view, Montlhéry

at the time of its foundation depended first on the rural district

of Linas. But when the town had taken importance, that is to say

in the first years of the fourteenth century, the seat of the district

was transported from Linas to Montlhéry.

At this period, the built-up town of Montlhéry

was accrued principally in the neighborhood of the market and in

the direction of the road to Paris; several crossroads were again

becoming joined to the main street. Outside the old Port Baudry,

there was no longer the trace of the first enclosure which had connected

the town to the chateau. Therefore, with patented letters dated

July 9, 1540, the inhabitants obtained the permission to close at

their own expense, their town of walls, with drawbridge, towers,

graves, and barbicans, in order to protect themselves from the "bad

boys." So the town was then surrounded with walls and flanked

of towers. There are three principle doors by which we enter: the

Port Baudry, on the Linas side; the Paris door in the direction

of the capital; and the door of the Borde, opening on the access

leading in one direction to the castle and the other direction at

St. Michel-sur-Orge at Longpont. These fortifications, which were

built in haste, were probably erected with the debris of the first

enclosures of the castle.

On March 1, 1543, the royal commissioners bought

back the ground and seigniory of Montlhéry from Francois of Escars.

They sold it to Claude of Clermont, lord of Dampierre; but he did

not keep this domain for a long time, because on March 3, 1547,

the commissioners bought it back in order to give the title of promise

to the chancellor François Olivier. It was only in the following

year, 1548, that the chancellor of Leuville took possession of his

ground and seigniory of Montlhéry.

2.4.2 THE RELIGIOUS WARS (1562 -1590)

This history of Montlhéry during the religious

wars is very well-related by Jeannine Gaugue-Bourdu in her recent

article. Here is a brief summary: In 1562, when the prince of Condé

separated himself from the court and reassembled his army around

Orleans, he seized Montlhéry. To block from the notable Argis in

this way: "During the troubles of the League in 1562, Montlhéry

was taken by the prince of Condé and his religious followers."

The town was looted and the besieged castle became the general quarter

of the Calvinists who left it in order to ravage the surroundings.

The monasteries of Longpont and Marcoussis, neighbors of Montlhéry,

were "devastated, given over to the lootings and burnings."

Saint-Louis, the first chapel of the castle which appeared on the

engravings of Chastillon, was without a doubt devastated at this

moment. Until the end of the century, the castle was successively

passed over into the hands of the different parties in presence.

In 1585, the members of the League chased the troops of the prince

of Cond6 but the townspeople of Montlhéry, exasperated, killed the

captain and gave the town and the fortress back to Henri III. This

is the same Henri III who, on December 9, 1587, ordered the Montlh6xiens

to repair the fortifications of their town, which was a little closer

to being finished in 1589. During this same year, the Duke of Mayenne,

who commanded the League army, sent an emissary to the head of the

troop in Montlhéry with an order to establish himself there. The

provost of the town pointed out that the castle was "uninhabitable"

and welcomed Henri IV as its savior, on April 5, 1590. The king

made a new sojourn to Montlhéry at the end of the year. once he

left, the partisans seized the castle and the town was again devastated

and looted. The resistance of the townspeople was vigorous and they

succeeded to chase the partisans away. But the fortress, whose state

no longer permitted the installation of a regular troop, became

"rather a cause of danger than protection" and the governor

of Paris gave, in 1591, the authorization to the Montlherians to

place it in a state of neutrality and to raze it, if need be. It

was at this time that the principle fortifications of the esplanade

were demolished and the materials used to finish the repairs of

the enclosure walls of the town. On December 15, 1603, Jerome the

Maistre, esquire of Bellejambe, obtained by licensed letters from

king Henri IV, the authorization of taking the castle stones so

he could build his house at Marcoussis, which is two kilometers

from Montlhéry, and surrounded it with pits. However, he decided

to leave the dungeon alone. Even the nuns used the rubble of the

fortress to construct a chapel in Montlhéry.

2.4.3 THE LAST ENGAGIST LORDS (1603-1789)

Armand Duplessis, bishop of Lugon, who later became

cardinal of Richelieu, had acquired the ground and county of Limours

which fell under the jurisdiction of Montlhéry. In 1603, he learned

from the queen Marie of Médicis that the ground and seigniory of

Montlhéry was just placed for sale. This is how he became the seventh

engagist lord of Montlhéry. But in 1627, king Louis XIII wanted

to increase the privilege of his brother Gaston of Orléans. So he

bought from the cardinal of Richelieu his county of Limours and

removed him from Montlhéry so that they could be reunited at the

dukedom of Chartres, which was the domain of Louis XIII's brother.

Gaston of Orléans conserved the ground and seigniory of Montlhéry

until 1660, the date of his death. After the death of Gaston of

Orleans, king Louis XIV, by licensed letters dated June 19, 1662,

left to his widow, Marguerite of Orleans, the pleasure and the usufruct

of the Montlhéry and Limours domains. But she gave these same domains

back, with the exception of the Limours castle that she wanted to

live in, to Guillaume of Lamoignon, the first president of the Paris

parliament, who thus became the 10th engagist lord of Montlhéry.

At the death of Guillaume of Lamoignon in 1677, his widow became

Lady of Montlhéry and conserved the ground and seigniory of Montlhéry

until 1696. On July 18, Jean Phélippeaux, advisor of the state and

intendant of the Paris generality, became lord of Montlhéry.

In 1747, Jean-Louis Phélippeaux, knight and master

of the cavalry camps, succeeded his father in quality of an engagist

lord of Montlhéry. He died in Paris on December 13, 1763. Philippe

of Noailles, duke of Mouchy, was the last engagist lord of Montlhéry.

He took back the possession of his domain in 1764. On September

17, 1764, the count of Noailles set up a minute from the state of

the castle. Becoming proprietor in 1772, the count of Noailles was

given a second minute on the valuation of his Montlhéy domain. This

minute indicated the state of disrepair of the fortress and the

urban enclosure. In effect, Montlhéry experienced some growth. The

door of Paris was knocked down in 1757, allowing the loaded cars

to return from the harvest. Finally, the pits were converted to

gardens in 1767 and 1771. The marshall of Mouchy, count of Noailles,

had married the daughter of Louis of Severac, marquis of Arpajon.

When her father died, the countess of Noailles, who was his only

heiress, brought to her husband: Arpajon, Saint-Germain, and the

Bretonni6re, all of which constituted the marquisate of Arpajon

from a recent foundation (1720). The marshall dreamt of joining

these grounds to his Montlhéry domain to set it up as a dukedom,

but then the French Revolution broke out. Stopped during the Terror,

the marshall and his wife were decapitated on June 17, 1794.

2.5 MONTLHÉRY FROM 1789 TO TODAY

2.5.1 The Restoration of the Castle (1842-1995)

The family of Noailles claimed ownership of the

tower and outbuildings. They started, at the Restoration, a judiciary

claiming against the State, but after a long process their claim

was dismissed. On April 5, 1842, they set up a minute from the State's

possessive hold of the tower. The tower was then classified with

other historic monuments and left to the care of the town of Montlhéry.

In July 1842, the municipal administration of Montlhéry acquired

the neighboring grounds which, in the past, depended on the castle

to convert them into walking grounds. The first of the architects

sent by the commission for historic monuments to consolidate the

tower and establish the restorative works was Hector Labrouste.

He began on May 20, 1842 to restore the walls of the turret of stairs

for lack of being able to reconstruct the vaults of warheads from

the first two levels of the dungeon. He also converted the terrace

just as they really were. He finished these works in 1846. The architect

Garrez continued after him in 1847. He constructed the footbridge

linking the two interior stairs of the tower at each floor. He repaired

the gap in the enclosure wall to the left of the large tower. He

also cleared the tombs of the enclosure and converted the principle

door with an iron railing for security measures. His works were

achieved in 1849. In 1878, the mayor complained about the deterioration

of the summit terrace to the prefect of Seine-et-Oise. At his request,

the commission of historic monuments ordered the architect Naples

to quote an estimate for the restoration of the tower. Then, he

was weighed down with the restoration itself, knowing that he would

carry out the plans until January 1881. The architect Selmershein

followed suit to achieve the work of his predecessor, who died.

He finished in 1889. There is nothing notable to report until 1934

... On June 20 of this year, lightning struck the top of the tower.

Berthod, chief-architect, demanded an emergency credit for 4100

francs to repair the parapet and the weakened superior terrace.

The works of restoration and protection against lightning were carried

out in 1937. The German troops of occupation left the tower of Montlhéry

in a sad state. Several series of restorative works were then necessary:

replacement of the footbridge, filling of wells... The sequel of

the archives say that the growing number of break-ins done on the

site carries the necessity of naming a residence caretaker. Since

1944, Monsieur Gérard Goudal, architect to the local office of the

Ministry of the Environment (DDE), is in charge of the restoration

of the tower which is in danger of collapsing...

2.5.2 THE SCIENTIFIC UTILIZATION OF THE MONTLHÉRY

FORTRESS (1822-1914)

After

the great revolutionary torment and the wars of the Empire, a calm

came over all the region. The old tower, abandoning its warrior

vocation, became a place for walking, and also found a new use in

scientific research. In 1822, the scientist Arago used the dungeon

for his experiments on the speed of sound.

In 1823, a Chappe telegraph station was

installed on the top of the esplanade. It receives signals from

Fontenay-aux-Roses, to transmit them to Torfou and beyond to Spain.

In 1839, a second telegraphic apparatus was edified at the top of

the tower. This was removed in 1854. In 1874, on June 5, Cornu and

other scientists used it to measure the speed of light between the

dungeon and the Paris observatory by installing a glass at the top

of the tower on May 7, 1914, Monsieur Defieber tried a model parachute

recess from the top of the dungeon. After

the great revolutionary torment and the wars of the Empire, a calm

came over all the region. The old tower, abandoning its warrior

vocation, became a place for walking, and also found a new use in

scientific research. In 1822, the scientist Arago used the dungeon

for his experiments on the speed of sound.

In 1823, a Chappe telegraph station was

installed on the top of the esplanade. It receives signals from

Fontenay-aux-Roses, to transmit them to Torfou and beyond to Spain.

In 1839, a second telegraphic apparatus was edified at the top of

the tower. This was removed in 1854. In 1874, on June 5, Cornu and

other scientists used it to measure the speed of light between the

dungeon and the Paris observatory by installing a glass at the top

of the tower on May 7, 1914, Monsieur Defieber tried a model parachute

recess from the top of the dungeon.

|